Court docs show pattern of unlawful CPD & local drug unit investigations

"I fear this is becoming a pattern. Like a case recently in front of me (...) this case represents yet another failure of the Charleston PD & MDENT to act within the confines of the Fourth Amendment."

By DOUGLAS J HARDING

Federal court documents obtained by the West Virginia Holler reveal a pattern of unconstitutional drug-related investigations conducted by the Charleston Police Department and the Metropolitan Drug Enforcement Network Team (MDENT).

“I fear this is becoming a pattern,” a memorandum opinion signed by U.S. District Judge Joseph Goodwin states. “Like a case recently in front of me (…) this case represents yet another failure of the Charleston Police Department and MDENT to act within the confines of the Fourth Amendment.”

That opinion was filed April 28 this year in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia and deals with an investigation which, ostensibly, began in October 2019, when a CPD detective on assignment with MDENT applied for a search warrant in Kanawha County.

Although a local magistrate issued a “sweeping warrant” authorizing detectives to search the home of a Charleston resident, Judge Goodwin granted a motion to suppress evidence seized from the home, on the basis that CPD and MDENT failed to establish probable cause and violated the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protecting people’s rights against “unreasonable searches and seizures.”

“In the same way that even a small child could not sit on a stool with three rotten legs, the magistrate’s finding of probable cause cannot be supported by the three dubious justifications provided by the government,” a court document states. “I find that there was no substantial basis for the magistrate’s conclusion that probable cause existed.”

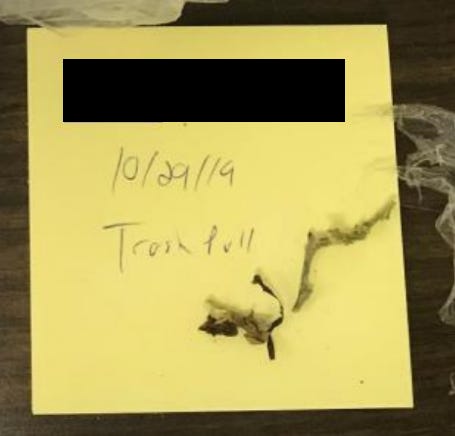

One of the grounds for probable cause cited in the warrant application filed by a CPD detective states that the detective “conducted a trash pull investigation of the (…) residence and discovered ‘multiple marijuana stems.’”

A “trash pull” is a type of investigation when law enforcement officers rummage through an individual’s garbage after it has been taken outside the home for collection. Trash pulls are common in drug-related investigations and generally seek to uncover evidence of illegal drug use or distribution.

Judge Goodwin’s opinion states that, “Other items discovered during the trash pull were listed, but the warrant application made no effort to explain their connection to the offense being investigated: possession of marijuana.”

Another of the grounds for probable cause cited in the warrant application states that a CPD officer “received information” that someone at a local residence was distributing large amounts of an illegal drug.

However, the reference court document states:

“[Detectives] did not include a single detail about the original source of this information. Was the information from yet another police officer? An anonymous tip? Was the information merely overheard in an elevator? No one reviewing the warrant would have any way of knowing where this information came from or when [an officer] received it. This is unacceptable. When applying for a search warrant based on hearsay, the applicant must include facts in support of the information’s reliability and accuracy. [Detectives] did no such thing here…”

The final of the grounds for probable cause cited in the warrant application states that detectives conducted a “controlled buy” of illegal drugs, which an individual of the local residence was “involved with.”

According to referenced court document:

“The person being investigated during that buy was observed walking through the fenced yard of the (…) residence. That is the extent of the involvement. No one ever saw that person enter or exit the home. That person merely walked through the fenced yard.”

As such, the only legitimate grounds presented for the search warrant were the few marijuana stems a detective collected while digging through garbage found outside a resident’s home.

Judge Goodwin states:

“[The detective] was aware of how very scant the marijuana evidence was in the trash pull. [The detective] could not reasonably have believed that the three tiny scraps of marijuana in the trash—unable to cover even a corner of a Post-it note—could support the idea of ongoing or recurrent activity in the home. None of the additional facts known to [the detective] are sufficient to make his reliance on the warrant reasonable.”

Judge Goodwin concludes that the warrant issued for referenced investigation was “unreasonably broad, bordering on a general warrant, to investigate the possession of marijuana. It authorized the search of electronic devices and financial records that have no connection to the offense of marijuana possession.”

Judge Goodwin stated the same exact conclusion, word-for-word, in another court document filed April 22 this year and dealing with an investigation that occurred in March last year.

That court document describes an investigation conducted mainly by a detective of the Nitro Police Department on assignment with MDENT.

The detective filed an application for—and was eventually issued—a search warrant in March last year on the basis that, two months earlier, “he had ‘received information that [an individual] was involved in the distribution of [illegal drugs]’” and had been arrested years ago for possession of marijuana.

Additionally, officers conducted a trash pull investigation, during which they collected “several packages of cigarillo’s [sic] (…) and a green stem which appeared to be a marijuana stem.”

Judge Goodwin’s analysis states:

“First, though [a detective] was aware of the actual source of this information, he was also aware that the confidential source had provided the tip two months prior to the warrant application, that this source had never provided reliable information before and that the source had skipped town the month before. Next, [a detective] was aware that he had set up a pole camera in front of [an individual’s] home, surveilled [referenced individual’s] home for an entire month and observed no suspicious activity. None of these additional facts known to [referenced detective] are sufficient to make his reliance on the warrant reasonable.”

Nevertheless, the warrant was issued and the defendant’s home was subsequently searched in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

The court document states:

“The magistrate then issued a sweeping warrant authorizing MDENT officers to search the entirety of [an individual’s] home for evidence of possession of marijuana including, but not limited to, electronic devices, books and financial records, photographs and address books.”

Additional court documents obtained by the West Virginia Holler show similar patterns of CPD, MDENT and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) conducting blatantly illegal investigations for drug-related activities.

One of the documents, filed in February this year and dealing with an investigation conducted in October last year, shows a different judge at the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia granting a motion to suppress evidence based on a similar Fourth Amendment violation.

The document states that a DEA officer applied for a search warrant on the basis of unsourced and unsubstantiated reports that “a black man had recently moved into [an] apartment, [where] the source of information (SOI) noticed a lot of people making short visits to the residence.”

The DEA officer also conducted a trash pull investigation, during which he collected “five plastic bags with the corners removed, three plastic bag corners and two plastic straws.”

Again, a Kanawha County Magistrate judge issued a warrant based on the application, authorizing detectives to search the defendant’s home without probable cause—another clear violation of the Fourth Amendment.

A footnote in referenced court document states, regarding the information upon which the search warrant was issued to detectives:

“Because the lack of evidence of criminal activity is sufficient to resolve the motion to suppress, there is no need to delve into an analysis of the lack of evidence of the SOI’s reliability. However, particularly in absence of direct evidence of criminal activity, a tip that begins by informing the officer that a Black man recently moved to the area should raise a red flag. There is a risk that the informant’s suspicions are based more on an assumption that a Black man is a criminal rather than the interference that heavy traffic with short visits must be drug activity.”

A final court document obtained by the West Virginia Holler was filed in May this year and deals with an investigation conducted in March 2018.

The document describes a situation during which MDENT detectives were conducting surveillance at the Greyhound bus station in Charleston.

According to the document, a detective witnessed an individual “stand in the back of a southbound bus as it arrived in the station and exit quickly, which he considered suspicious.”

The detective notified his partner, who then witnessed the individual entering a vehicle and sitting in the passenger seat. The detective testified that he called in the out-of-state license plate on the vehicle and learned the vehicle’s registration was expired. The two detectives proceeded to conduct a traffic stop without using a dash camera and for which no body camera footage has been made available.

During the traffic stop, one detective issued a warning ticket for the expired registration before returning to request consent for a search of the vehicle, for which the driver of the vehicle denied his permission.

The detectives proceeded to conduct a “dog sniff” of the vehicle with the assistance of a K-9 trained to detect the presence of certain illegal drugs, including heroin.

The court document states one of the detectives testified that: “A positive alert (during the ‘dog sniff’) could be any obvious change in behavior, such as tail wagging, sitting, intense sniffing or excitedness. His recollection is that [the dog] alerted by sitting down outside the front passenger side of the vehicle.”

The defendant in the case argued that:

“The stop was unsupported at its inception because, in his view (…) the report indicates that the officers did not learn that the registration was expired until after stopping the vehicle. He further contends that the scope and duration of the stop were impermissibly extended beyond the purpose of issuing a warning citation for expired registration. In addition, he argues that the United States has not adequately demonstrated that [the dog’s] training, certification and reliability were adequate to support a search. He argues that the methods of alerting are overly subjective, that [the dog] is not trained or certified in identifying prescription opiates and that any dog sniff designed to detect prescription opiates would be improper because such substances are typically possessed as legal medical prescriptions.”

While the court avoided making a decision related to the legality and reliability of the “dog sniff,” it granted the motion to suppress evidence seized during the search on the basis that officers illegally prolonged the traffic stop to investigate unrelated activity without probable cause for doing so.

The court’s conclusion states:

“After completing all tasks necessary to effectuate the purpose of the traffic stop—citing [an individual] for his expired registration—the officers had no further justification for continuing the seizure of [both individuals]. At the point that [detectives] had completed the purpose of the stop and returned to the vehicle to to further question [passenger], the seizure was impermissibly prolonged. At that juncture, further questioning was not necessary to either complete the purpose of the stop or to insure officer safety. Its purpose was to investigate an unrelated criminal matter.”

The West Virginia Holler is an affiliate of The Tennessee Holler and is powered, in part, by West Virginia Can’t Wait.

Follow the Holler on Twitter @HollerWV and Instagram @WVHoller. We're on Facebook too! Follow writer Douglas J. Harding @douglasjharding.