Educators speak against classroom censorship bill

"Revising our past in the way being suggested is the worst possible path... Letting politicians, special interests & corporations edit our history like a gossip column won’t get you what you want."

By DOUGLAS J HARDING

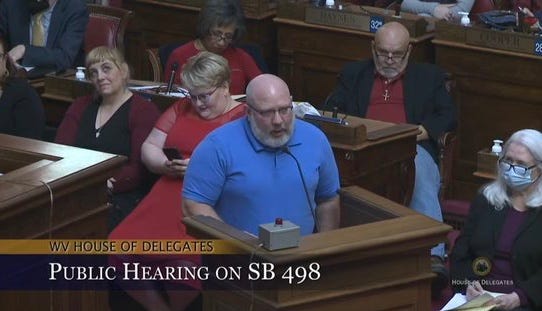

Educators who attended Monday’s public hearing regarding Senate Bill 498, the “Creating Anti-Racism Act”—which would greatly restrict educators’ freedoms to teach students about race and identity—said the legislation would not create “anti-racism,” but instead would stifle free speech and institutionalize white-supremacist bigotry.

The Charleston Gazette-Mail reported that Monday evening, following the morning’s public hearing, the House Education Committee amended the legislation to “no longer affect colleges or sex discussions,” before advancing it to the House Judiciary Committee.

A similar bill, House Bill 4011—the “Anti-Stereotyping Act”—was introduced in the House of Delegates last month before dying in committee following a public hearing during which 27 of 29 speakers said they opposed the bill. Del. Chris Pritt (R- Kanawha, 36) was the lead sponsor of HB 4011.

SB 498’s lead sponsor is Sen. Patricia Rucker (R- Jefferson, 16). The bill passed the Senate earlier this month by a vote of 21-12, with one senator marked as absent. Del. Shawn Fluharty (D- Ohio, 03) filed a motion to reject the bill from the Senate, which failed in a 21-73 vote, with six delegates marked as absent.

Of the 28 speakers in attendance at Monday’s public hearing, 24 spoke in opposition to SB 498 and 4 spoke in favor of the bill.

“I’ve spent a great deal of time in the classroom. I taught at West Side Middle School, which was Stonewall Jackson Middle, that was located on a former plantation next to a former plantation house where slaves were bought and sold. And I taught American history on the Civil War,” said Howard Swint, who has served as an emergency educator during the COVID-19 pandemic. “I would suggest to you that even at middle school, not to mention higher education and secondary [education] as well, that these students have a great interest in the topics that you would presume to censor with this bill.”

Swint referred to the legislation as the “Censorship in Education Bill” and said the bill aims to address a manufactured controversy from the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).

“From a historical perspective, I think this is just a wave of southern white privilege bigotry rolling through government—you know, the kind that put the Stonewall Jackson statue on our [Capitol] grounds 100+ years ago when people wore ‘Lily-white’ buttons and talked about that as the higher good,” Swint said. “The same people, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, put a bust in 1959 in our [Capitol] Rotunda. And now I’m speaking in the [House] Chamber, where last year, a bill was passed that would protect those monuments (…) This is a form of bigotry being institutionalized by government.”

Kenyatta Coleman Grant, a community organizing coordinator for the West Virginia Coalition Against Domestic Violence, said she spends much of her time educating and raising awareness about issues impacting marginalized communities. She said she facilitates “diversity trainings as cultural competency, implicit bias and allyship to our domestic violence programs, other nonprofit organizations and law enforcement agencies.”

“We all want to create anti-racism, however we all know this bill does not have that as a goal and, if passed, will do serious damage to everyone—especially our students,” Grant said. “[The teaching of] history must be accurate and honest and raw because that is the only way we can avoid pushing our mistakes onto our children. We all want to reminisce about the great path and heroism of our forefathers and the challenges we have overcome (…) However, if we don’t acknowledge the valleys along with the peaks, we risk losing all credibility. We delude ourselves into a false narrative that only benefits our pride—not our intelligence.”

Grant said the proposed legislation would prevent educators from teaching students about essential times and people impacting American and West Virginia history and would only worsen already deeply-entrenched political divisions.

“To exclude the teachings of slavery, you can’t tell the stories of great Americans like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass or great West Virginians like Booker T. Washington. Without the story of Jim Crow, we can’t tell the story of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King or great West Virginians like Herbert Henderson,” Grant said. “History must tell what we have overcome, but it must also acknowledge what we have learned. Revising our past in the way that is being suggested is the worst possible path (…) Letting politicians, special interests and corporations edit our history like a gossip column won’t get you what you want. It will only add to the divide.”

Kitty Dooley, a local attorney and former member of the West Virginia State University Board of Governors, said there are countless other more effective ways to ensure West Virginia public policy reflects anti-racist values.

“I’ve been practicing law in the state of West Virginia for over 30 years and have the privilege of teaching both history of the United States and implicit bias as it impacts people in this world. If the public policy of West Virginia is to be ‘anti-racism,’ as it states in this bill, then we need to drop the idea about teaching concepts. We need to take the school board and the school system and the teachers off the hook,” Dooley said. “If we’re serious about being an anti-racist state, there are many things that we can do, beginning with this body, with this state, with the businesses that belong in this state, with the criminal justice system and all of the other systems that impact African-Americans disproportionately. So, if that’s the reason, then let’s start over.”

Dooley said the likely primary intent of legislators is not to ‘create anti-racism,’ but to subvert academic freedom and to prevent the teaching of certain parts of history.

“What portion of history are we afraid to teach our children and our students in higher education?” Dooley asked. “We have a proposal to prohibit instruction of concepts that make some people feel uncomfortable. As a black woman who matriculated through the schools in West Virginia—and as an attorney—if this is the standard, then you’re giving me a cause of action for every discussion of the enslaved African-Americans, of the Confederate’s glorification of lynching, [of] domestic terrorism following Reconstruction, of Dred Scott [v. Sandford] and Plessy v. Ferguson, [of] Civil Rights Era firehoses and the dogs that were let loose on people who looked like me.”

Nicole McCormick taught elementary and middle school students in southern West Virginia for 13-and-a-half years and is a member of the West Virginia United Caucus, which unites several local education unions. McCormick noted that SB 498, if passed, would result in college credits being taken away from local high school students taking Advanced Placement courses.

“I feel like sometimes in West Virginia, we tend to listen to folks outside the state more than we do the people inside,” McCormick said. “So, let me put this out there: AP—Advanced Placement—has released a statement saying that if bills like this are passed, they will revoke their name on college classes that are offered to high school students during the day. So, if this passes, you are hurting high school students who get college courses for free.”

The College Board released a statement last week declaring:

“AP opposes censorship. AP is animated by a deep respect for the intellectual freedom of teachers and students alike. If a school bans required topics from their AP courses, the AP Program removes the AP designation from that course and its inclusion in the AP Course Ledger provided to colleges and universities.”

McCormick also said many students in West Virginia are not first introduced to sensitive and potentially divisive concepts at schools, but actually are forced to experience those concepts in their daily lives.

“Our children live in this world. They see what goes on. Our children who are part of the LGBTQ+ community or have brown skin understand what is happening around them. We are not introducing something that they have never been introduced to before. We are not scaring them. They have access to the internet. They live in neighborhoods where they understand what a gun sounds like. They know what it’s like to be hungry,” McCormick said. “It’s also important that we recognize that some things are uncomfortable—and that’s OK. I don’t feel guilty for who I am, but I would also like to be able to learn compassion for people [because] I will never walk the life that they walk.”

Barry Holstein said he supports the bill because he believes that books such as Angie Thomas’s ‘The Hate U Give’ include subjects that are too complex and words that are too mature for high-school students to discuss and comprehend.

“What part of eleventh grade standards makes it OK to utilize lesson plans from an organization called Learning for Justice, an arm of the Southern Poverty Law Center? What part of the standard says that eleventh grade students in West Virginia should be reading a book titled ‘The Hate U Give’ about a young black girl who sees her longtime friend shot and killed by a white cop without cause and uses the F-word 89 times?” Holstein asked. “[‘The Hate U Give’] progresses to openly support the ideas of white privilege, perpetuate stereotypes, suggest white cops frequently kill black men for no reason and that systematic racism exists in all aspects of life. I, personally, really liked that story. It’s a great story, but I felt that it discussed some complex, adult social issues [and] contained horrible language, and therefor, the selection of the book is suspect-at-best for the eleventh grade.”

Holstein also read an alleged direct quotation from the book’s author, Angie Thomas. The alleged direct quotation that Holstein read goes as follows:

“My job as an author is to write books for kids that make the adults uncomfortable because that’s what kids need.”

“I respectfully disagree that this is what kids need from our schools,” Holstein continued.

Rosemary Hathaway, an English professor at West Virginia University who opposes the legislation, digressed momentarily from her prepared remarks to address Holstein’s concerns.

“In addition to the quote [previously mentioned], Angie Thomas also said that, ‘It’s a privilege if your greatest concern for your child is that they will have to read about police violence rather than experience it,’” Hathaway said. “I am the proud daughter of parents who both graduated from West Virginia high schools and the granddaughter of two West Virginia public school teachers. From all those people, I inherited the values of openness and growth: precisely the values that this bill works against.”

The West Virginia Holler is an affiliate of The Tennessee Holler and is powered, in part, by West Virginia Can’t Wait.

Follow the Holler on Twitter @HollerWV and Instagram @WVHoller. We're on Facebook too! Follow writer Douglas J. Harding @douglasjharding.