Remembering Blair Mountain

More and more is being taken from us every day, and now they’re trying to take away our history, our reminder to ourselves of what’s possible and what we can win when we come together to fight for it.

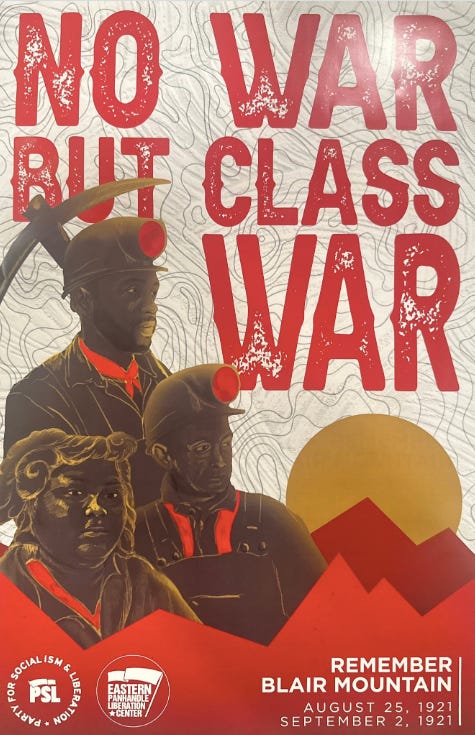

The following is a speech by Robert Gillette, director of the Eastern Panhandle Liberation Center in Martinsburg, WV. The speech was given as part of “Remember Blair Mountain: Celebrating the Largest Labor Uprising in US History,” an event held in Shepherdstown, WV, organized by the WV branch of the Party for Socialism and Liberation, the ANSWER Coalition, and the Eastern Panhandle Liberation Center. The speech, in full:

It is important that we remember our history here, because West Virginia has such a deep organized labor history. Really what defines West Virginia, in a lot of ways, are the people here and their ability to stand up and organize themselves against atrocious conditions. We have to talk about Blair Mountain. We have to remember it. It is important that we all know what happened.

August 1921, 103 years ago, over 10,000 miners marched up Blair Mountain to fight an army of private guards paid by the coal mine companies—which is exciting on its own, but it didn’t come out of nowhere. This was a culmination of 30 years of organizing, 30 years of really terrible conditions imposed on those miners, imposed on the people who brought that coal out of the ground, people who made a lot of money for another very small group of people. These men, these families, were mostly immigrants—a lot of Italian immigrants. Think about our famous foods [such as] pepperoni rolls. That’s because those Italian immigrants needed something [to eat] that would last all day down in those mines. So, our history, even the food we eat, is built on that tradition, built on that history. These men—Italian, Polish, Irish—were sold on a life of getting paid and having homes up in the mountains, things they couldn’t find in the places where they were coming into this country. So, they went up into the mountains, and they headed down into the mines. And they didn’t just head down into those mines [on their own]—there were armed guards holding guns. I suggest you look to the Mine Wars Museum for more information on that, because it’s really telling when you see the repressive nature of just going to work—just what it took to go down into those mines.

So, for 30 years, the UMWA worked, starting in the northern part of the state, on figuring out how to unionize. [They said] these conditions here are terrible. These people are ripe for organizing. So, they moved through the northern part of the state, and they faced a lot of pushback, a lot of repression. The Baldwin-Felts and the Pinkertons would murder unionizing miners. They would evict families, forcing them to live in tents on the mountains. I don’t know if you’ve ever been up on the mountains in northern West Virginia in the winter, but it’s very cold. Imagine having to live up there in a tent. The rail company actually even built an armored rail car that would go up into the mountains and shoot into those tents. These were tents filled with families: children, women, people who had been evicted. And what were they evicted for? These people had to live in company towns. That means the town owned their house. The town owned the store they had to shop in. And they were paid not in money but in scrip. They went down [into the mines] and they broke their bodies, they got black lung, they faced cave-ins, they watched their friends die, and they didn’t even get paid in money they could take [and use] anywhere else. They got paid in scrip, and they had to go to the store that the company owned and got to set the prices at. And if you couldn’t pay, and you talked about unionizing, then you were out: Nowhere to go. They shipped you up there on the train, and they didn’t give you a ticket back. They didn’t want you anymore. They just pushed you out into the cold. People were living in these really terrible conditions. So, that really made unionization not just something that these people wanted to do for a paycheck, but something that they needed to do to survive. [Something they needed to do] to survive against a capitalist system that was made to pull the most profit—through their exploitation, through their suffering, through their hard work—off their backs. So, we always want to remember what these people did. That coal was what lit the lights of this country. That coal was what fired the steel forges that made the steel that this country is built on top of. And these men never even got to see that. They lived in hollers being oppressed literally every day by armed guards.

So, as World War I set in, industry boomed. We needed more and more coal, and that started to drive organization through the northern and middle part of the state. But still, the southern part of the state wasn’t coming along. So, the UMWA was still trying to keep pushing as they moved south. After the end of World War I, a depression started to set in. War is good for business, right? So, when we didn’t have war, the money started to dry up. And who pays first? Did the bosses take a pay cut? No. The workers had to pay for it. The workers had to lose their jobs. The workers had to face contract provisions, [such as] the coal companies paying them by the weight of the coal they brought out of the ground. But the coal company would weigh the coal. So, that actually led to a mine war that precedes Blair Mountain.

The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike happened about ten years before Blair Mountain. The unionized miners there got together, and their demand was: Let us weigh the coal that we pull out of the ground—which would have cost the coal companies 15 cents per worker per week. Instead, the coal companies sent in the Baldwin-Felts agents, who were a private security company who arrested and murdered miners who were evicted. So, people were just asking to get paid [and saying], “Just share a little bit of what we earn with us.” And they faced absolute repression. And that led to a mine war. There was a battle. And [the miners] won. They ended up getting the union that they were fighting for. But it was hard. And that ended with the State of West Virginia forming the West Virginia State Police to come in and shut the union down. So, those miners had to live under martial law. And that martial law was imposed by the very same private police force, which was then deputized by the state. The state goes hand-in-hand with the companies. [The private police forces] were literally wearing Baldwin-Felts badges, and they would take those off, and then put on their state badges, and so now they were the police. That sounds like a conflict of interest to me. Does that sound fair to you? The same guys who shoot you and put a gun to your back and tell you to go down into the mountains are also your state police. That’s your state, that’s your democracy, saying to you, “Actually, you don’t have a voice here. You don’t even deserve ten more cents a day. You deserve to go down into the mountain, and if you don’t go down in there, then you can go live in a tent on the side of the railroad track.” It’s really important to think about this context. These miners didn’t just march up in there being violent, saying, “We want what we want and we’re going to take it.” They worked. They were doing the hard work for it. And they were treated so terribly—so incredibly repressive. So, this is the system that started the violence. [This system] had a monopoly on violence that it visited upon these coal miners for three decades straight before we finally got to the events of Blair Mountain.

So, if we go back to about a year before Blair Mountain, Sid Hatfield, the sheriff in Matewan—who was actually a pro-union sheriff—deputized several miners. And then the Baldwin-Felts agents came into town. And these specific Baldwin-Felts agents were actually known to have already committed a massacre out in the coal mines of Colorado: the Ludlow Massacre. These people were known to have murdered other miners across the country, so in solidarity with them, Sid Hatfield organized these miners and went to [the Baldwin-Felts agents] and said, “You all are under arrest.” And what were the Baldwin-Felts agents doing then? They were going out and evicting miners from their homes, kicking women and children out into the cold. So, [Sid Hatfield] said, “You’re under arrest,” and the Baldwin-Felts agents pulled out an arrest warrant and said, “Actually, you’re under arrest.” And so, there was some confusion, and they started shooting at each other. Seven of the Baldwin-Felts agents were killed. Three of the miners were murdered. This is called the Battle of Matewan, and this really incited the miners. Because for the first time they realized, “We can actually fight back against this. We don’t have to just take this lying down. Somebody’s got to stand up for us, and the only way we’ve ever stopped this is by fighting back against this violence that is visited upon us every day.”

So, that kicked off a year of Sid Hatfield working to arm these miner camps. And we have to remember, these weren’t just people being allowed to live in tents. These people were being bombed. These people were being shot at by armored train cars. These people were being raided by the police constantly. And any time they went into town to unionize, they were arrested. So, they started arming themselves to protect themselves from this very repressive system. After a year of all this growing, the union starts to move into Mingo County, where it had never had a foothold, which was very exciting. And the coal companies did not like this. They did not want another unionized coalfield. They only wanted to make as much money off those workers as possible. So, the violence ramped up. And as Sid Hatfield and his wife walked up the steps of the Mingo Courthouse for the trial for the Baldwin-Felts agents that were killed in self-defense, the Baldwin-Felts agents waited at the top of the stairs and shot him as he was unarmed walking into the courthouse. And as you would expect, the miners were not happy about this. [Sid Hatfield] was their man, and he was murdered in cold blood: Another, in a long history of miners and pro-union men being murdered. And that incensed the miners, all these conditions together. This was an icon of what it meant to stand up and fight back, and he was murdered brutally as he was marching into the courthouse. There was no protection from the police. Again, the state did nothing to protect miners. And so, the miners said, “Enough is enough.”

Then labor leaders like Mother Jones and [Frank] Keeney came in and started rallying the union members and saying, “We’ve got to do something about this.” So, the miners got themselves together and armed themselves, and over 10,000 of them marched on Mingo County. They marched from the unionized coalfields down into Mingo County. And on the other side, the sheriff, the state police, and the private police formed an army, and they went up on the mountaintop and started digging trenches on Blair Mountain, getting ready for this fight. And on August 26, the Battle of Blair Mountain was almost avoided. The miners went to a meeting to speak with representatives of the state and representatives of the coal company, and they came to an agreement. While they were doing that, the sheriff up on the mountain heard about this and decided to go down into the town and start shooting women and children and other miners. So, then the battle was on.

This was the largest uprising in American history after the Civil War. 16,000 miners marched up to Blair Mountain, and the battle began. The miners fought their way up that mountain. They skirmished for a few days until federal troops were sent in. And many of these miners were World War I veterans who had already gone and served this country. So, when they saw US Army troops, they said, “We can’t fight our own people. We just spent years fighting together. We can’t do that.” And they marched off the mountain. So, sadly, the Battle of Blair Mountain went down as a defeat in the short-term for union organizing in the area. But it is memorable, and it is so important to us now. And their memory, ten years later, sparked a labor movement that washed over this country and led to things like the New Deal, and unionization across the country tripled in numbers. West Virginia became one of the strongest union states for most of our history. Really, we only saw that end with the signing of NAFTA by Democratic President Bill Clinton. And many West Virginians will tell you this. The unions were the reason the Democrats were so strong. I always like to remind people that West Virginia was one of only six states to vote for Jimmy Carter over Ronald Reagan. We always get told we’re a Republican state, right? But we were a strong union state. Those unions got us to vote for Democrats. And the Democrats turned on us. And we lost a lot when we did that.

So, this is why it’s so important to remember: How did we win what we needed? We only win when we organize. We only win when working class people organize ourselves to fight for what we need. We only win when we have the bravery to stand up and say, “Enough is enough. We will resist the violence and terribleness of this capitalist system by organizing ourselves and the people around us.” We always have to keep Blair Mountain in our memory—we have to keep all the labor struggles in this country in our memory—because that is how we’ve won everything we have now: because unions organized and fought for it. Not because of what Democrats did or what Republicans did, but because of what we did. Because of what working class people like you and me did. We win only when we are brave enough to do this together, when we take our history into our own hands and we say, “This fight is ours and we are going to continue this fight. We are going to march on just like the miners who marched on Mingo. This is our country, these are our people, these are our homes, and we deserve better than what we have today. We deserve better than constantly rising prices. We deserve better than a country with the highest prison population on Earth.” We deserve better than this, and we can only get that through organizing like those men on Blair Mountain who we still think about today. It is so important that we keep that memory with us and keep that memory alive.

Blair Mountain has a special place in my heart. The only reason I became an organizer at such a young age is because I learned about Blair Mountain in my eighth-grade West Virginia studies class. But we know today that we aren’t even allowed to teach this history in schools anymore. When you drive around here today, you’ll see these license plates that say, “Friends of Coal.” But that is a lie. That is a lobbying group that lobbied to have our own history taken out of our history books. So, we don’t even get to learn our own history. They will take anything from us. They take our work. They take our pay. Right now, our housing prices are going up. I’m from this town and I can’t even afford to live here. More and more is being taken away from us every day, and now they’re even trying to take away our history, our reminder to ourselves of what’s possible and what we can win when we come together to fight for it. So, that’s why we’re going to remember Blair Mountain. And we’re going to carry that history and that passion and that care for our community into everything we do today.

WV Holler links: https://linktr.ee/hollerwestvirginia